For more than a generation, American defense policy rested on an assumption so deeply embedded that it rarely needed to be articulated: the United States could afford to be everywhere. The Cold War had ended without a successor. No rival possessed the combination of economic scale, military reach, and ideological ambition necessary to challenge Washington across multiple theaters. The international system, though often turbulent, appeared fundamentally manageable.

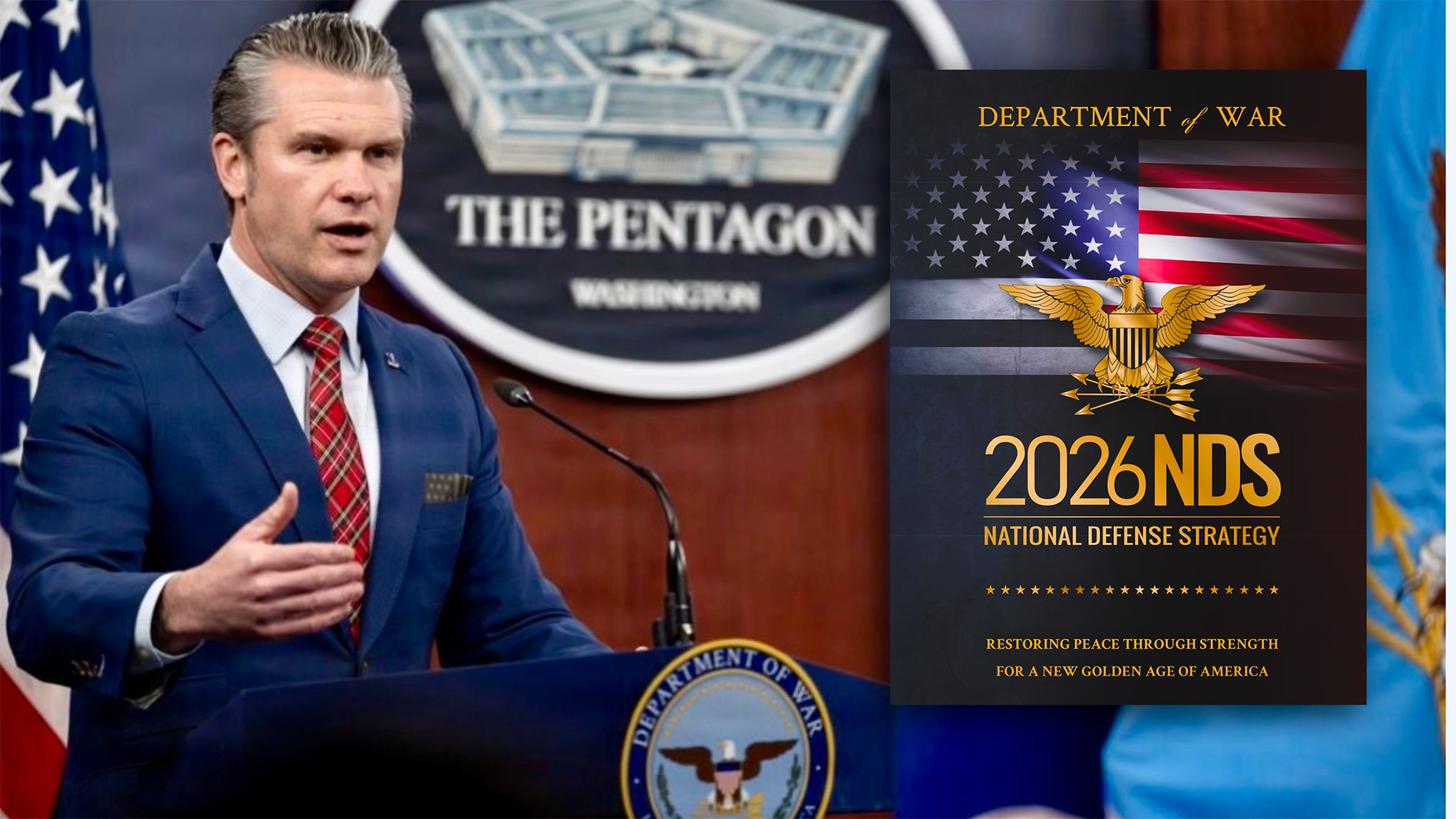

The 2026 U.S. National Defense Strategy suggests that this era is over.

What distinguishes the document is not simply its identification of China as a central competitor, or its emphasis on military readiness and industrial renewal, both familiar themes by now, but a more fundamental reordering of priorities. The Strategy abandons the notion that American security is naturally aligned with global stability. Instead, it advances a view of international politics defined by scarcity, competition and hard choices. The United States, it argues, must now decide where power truly matters—and where it does not.

This is a document shaped less by optimism than by arithmetic.

At its core is a rejection of universality. The Strategy insists that U.S. interests are finite, that resources are limited, and that credibility cannot be sustained through presence alone. The task of American defense planning, it argues, is no longer to manage the international system as a whole, but to concentrate power where failure would be catastrophic: the homeland, the Western Hemisphere, and the Indo-Pacific.

The shift is subtle but consequential. For decades, U.S. military posture was organized around reassurance of allies, institutions, and global norms. The 2026 Strategy is organized around endurance.

Nowhere is this more evident than in its treatment of the American homeland. Once treated as an inviolable rear area, the homeland is recast as an active theater of defense. Missile barrages, drone swarms, cyber operations and undersea threats are no longer hypothetical futures; they are planning assumptions. The 2026 Strategy places renewed emphasis on missile defense, nuclear modernization, cyber resilience and continental surveillance, framing sovereignty itself as a contested domain.

This focus extends outward, reshaping the United States’ relationship with its immediate surroundings. The Western Hemisphere, ong rhetorically important but strategically neglected, returns as a central concern. The document speaks openly of restoring American military dominance in the hemisphere and denying external powers the ability to project force into it. In language that echoes earlier eras, it frames this ambition as a modern corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, adapted to an age of missiles, networks, and long-range strike.

If the homeland is the foundation, the Indo-Pacific is the fulcrum.

The Strategy’s approach to China is notably restrained in tone and unsentimental in logic. Beijing is neither demonized nor accommodated. Instead, it is treated as a structural reality, an actor whose power must be bounded rather than transformed. The central operational concept is “Deterrence by Denial”: preventing China from achieving military dominance in East Asia, particularly along the First Island Chain, without seeking confrontation for its own sake.

This marks a departure from both Cold War containment and post–Cold War engagement. The goal is not victory, but equilibrium, a balance of power in which no state can unilaterally rewrite the rules of access to the world’s economic center of gravity. Negotiation remains possible, even desirable, but only from a position of strength.

Allies matter in this framework, but differently than before.

The Strategy is unusually blunt about burden-sharing. It calls for allies to contribute not symbolically but materially, setting a clear expectation that security requires sustained investment, measured in output as much as intent. Partnerships are no longer framed as permanent guarantees; they are conditional arrangements, calibrated to demonstrated capacity and willingness.

South Korea is singled out as an ally with both the means and the motivation to assume greater responsibility, particularly in relation to North Korea. The United States signals its intention to adjust force posture accordingly, rebalancing the alliance toward shared responsibility rather than unilateral protection.

Canada appears in the document in more restrained language, but its role is no less significant. The Strategy acknowledges Canada as essential to the defense of North America itself, particularly in aerospace, maritime, and undersea domains. As threats become longer-range and less geographically constrained, continental defense becomes inseparable from Canadian territory, infrastructure and capabilities.

What emerges, implicitly, is a vision of North America as a single strategic space, one in which early warning, domain awareness and industrial capacity are shared assets rather than national luxuries.

Europe, by contrast, occupies a quieter place in the document. Russia remains a threat, but a constrained one. The 2026 Strategy makes clear that while the United States will remain engaged, European allies are expected to take primary responsibility for their own conventional defense. The Atlantic alliance endures, but its center of gravity has shifted. The post–Cold War assumption that European security would be indefinitely subsidized by American power no longer holds.

Beneath all of these choices lies the document’s most consequential assertion: that power, ultimately, is material.

The 2026 National Defense Strategy treats the defense industrial base not as a supporting function, but as the foundation of military strength itself. Production capacity, supply chains, munitions stockpiles and industrial scalability are framed as strategic assets on par with fleets and formations. War, in this conception, is not a brief rupture but a prolonged test of endurance, one that rewards those who can build, replace and sustain faster than their rivals.

The Strategy also speaks openly of national mobilization, drawing parallels to earlier eras when industrial capacity proved decisive. It rejects the post-industrial illusion that technological sophistication alone guarantees advantage. Precision without volume, it implies, is not deterrence.

Taken together, the 2026 National Defense Strategy offers a sobering picture of the world as American planners now see it. Institutions matter less than capacity. Norms are fragile without enforcement. Peace is not presumed; it is produced.

This is not a call to perpetual war, nor an embrace of isolation. It is an acknowledgment that the conditions which allowed the United States to act as the system’s manager no longer exist. The task ahead is narrower, harder, and more unforgiving: to secure decisive advantages in the places that matter most, and to accept limits elsewhere.

History, the 2026 Strategy suggests, never stopped moving. It only waited for power to remember itself.

Forging Our Future Together: The New Era of U.S.-Japan Relations.

GX, DX, and AI innovation at Deloitte Tohmatsu Innovation Park

USJC (U.S. - Japan Council) annual conference in Tokyo